How is it that, before this summer, I'd never read C. J. Cutcliffe Hyne's

The Lost Continent: The Story of Atlantis? I'm glad to say that I've just corrected the omission. Published serially in 1899 and as a book in 1900, it bears the stamp of the best of H. Rider Haggard's novels, but stands alone in being set wholly within antediluvian times, apart from a ridiculous framing story that serves only to explain why the narrative begins and ends so abruptly.

The book seems not very well known or respected these days. E. F. Bleiler in

The Encyclopedia of Fantasy dismisses it in one sentence as "a stodgy dynastic romance that is now occasionally laughable." This, in the article on Atlantis; neither Hyne nor his novel have their own entry, and they are not mentioned in the article on Lost Lands and Continents. This judgment seems unduly harsh. Drawing heavily on Ignatius L. Donnelly's "nonfictional" work,

Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, published in 1882, it is a work of real power and imagination, and, one suspects, a major influence on the many pulp writers who explored prehistoric civilizations in their stories.

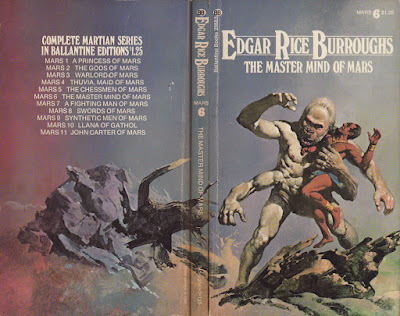

Hailed by Lin Carter and L. Sprague de Camp as the best Atlantis novel out there,

The Lost Continent was rescued from obscurity through its publication in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. Here is a scan of my copy's cover, with wrap-around painting by Dean Ellis:

The story opens in the Yucatan (although, sadly, this setting receives only a cursory glance), but most of the action takes place in the lost continent itself. The narrator and protagonist is Deucalion (as in the

Greek deluge myth), a successful viceroy and general called home by the beautiful, capricious, self-deified empress Phorenice. She intends him as her husband, a plan that ends in disaster, owing in part to Deucalion's extreme moral rigidity (in the Atlantean sense). The characters are stiff, the love-making awkward and underdeveloped, the plot strangely meandering. But if you want a good and robust late Victorian romance set against a backdrop of mythic splendor and prehistoric mystery, then look no further.

There's a sea-battle between solar-powered ships and plesiosaurs. There's a seductive empress who rides a colossal wooly mammoth through the streets of the capital. There's a labyrinthine palace in a giant pyramid lit by subterranean fires. There are secret passages. Superdrugs. Volcanoes. Premature burials. Pagan anathemas. Warrior priests. Hairy half-bestial invaders. Pterodactyls that swoop down to steal sacrificial victims. A doomsday escape vessel that seems a cross between the Ark of the Covenant, Noah's ark, and a seed bank.

The novel also shows a creative attention to weird little details, a quality often sadly lacking in later, more derivative fantasy. Consider, for instance, this grotesque description of Deucalion's lover, disinterred from the tomb where she has sat buried alive for nine years:

Her beauty was drawn and pale. Her eyes were closed, but so thin and transparent had grown the lids that one could almost see the brown of the pupil beneath them. Her hair had grown to inordinate thickness and length, and lay as a cushion behind and beside her head. [...] The nails of her fingers had grown to such a great length that they were twisted in spirals, and the fingers themselves and her hands were so waxy and transparent that the bony core upon which they were built showed itself beneath the flesh in plain dull outline. Her clay-cold lips were so white, that one sighed to remember the full beauty of their carmine. Her shoulders and neck had lost their comely curves, and made bony hollows now in which the dust of entombment lodged black and thickly.

Or again, the description of the superbly imagined ark:

A wonderful vessel was this Ark, now we were able to see it at leisure and intimately. Although for the first time now in all its centuries of life it swam upon the waters, it showed no leak or suncrack. Inside, even its floor was bone dry. That it was built from some wood, one could see by the grainings, but nowhere could one find suture or joint. The living timbers had been put in place and then grown together by an art which we have lost to-day, but which the Ancients knew with much perfection; and afterwards some treatment, which is also a secret of those forgotten builders, had made the wood as hard as metal and impervious to all attacks of the weather.

In the gloomy cave of its belly were stored many matters. At one end, in great tanks on either side of central alley, was a prodigious store of grain. Sweet water was in other tanks at the other end. In another place were drugs and samples, and essences of the life of beasts; all these things being for use whilst the Ark roamed under the guidance of the Gods on the bosom of the deep. On all the walls of the Ark, and on all the partitions of the tanks and the other woodwork, there were carved in the rude art of bygone time representations of all the beasts which lived in Atlantis; and on these I looked with a hunter's interest, as some of them were strange to me, and had died out with the men who had perpetuated them in these sculptures.

At every point the author shows a predilection for grandiose adventure, but tempers it with an attention to visceral detail:

Blood flowed from the mammoth's neck where the spikes of the collar tore it, and with each drop, so did the tameness seem to ooze out from it also. With wild squeals and trumpetings it turned and charged viciously down the way it had come, scattering like straws the spearmen who tried to stop it, and mowing a great swath through the crowd with its monstrous progress. Many must have been trodden under foot, many killed by its murderous trunk, but only their cries came to us. The golden castle, with its canopy of royal snakes, was swayed and tossed, so that we two occupants had much ado not to be shot off like stones from a catapult. [...]

I braced myself to withstand the shock, and took fresh grip upon the woman who lay against my breast. But with louder screams and wilder trumpetings the mammoth held straight on, and presently came to the harbour's edge, and sent the spray sparkling in sheets amongst the sunshine as it went with its clumsy gait into the water.

But at this point the pace was very quickly slackened. The great sewers, which science devised for the health of the city in the old King's time, vomit their drainings into this part of the harbour, and the solid matter which they carry is quickly deposited as an impalpable sludge. Into this the huge beast began to sink deeper and deeper before it could halt in its rush, and when with frightened bellowings it had come to a stop, it was bogged irretrievably. Madly it struggled, wildly it screamed and trumpeted. The harbour-water and the slime were churned into one stinking compost, and the golden castle in which we clung lurched so wildly that we were torn from it and shot far away into the water

Refreshingly, the narrator and other characters follow a pagan moral code wholly alien to modern social mores. Deucalion in particular shows utter unconcern with the lives of the peasant and slave classes, whom he plainly despises, and in fact openly reviles in several passages. (Slaves, incidentally, come chiefly from Europe.) Though odious, his attitudes greatly enhance the book's verisimilitude. The destruction of a continent and people to satisfy the zeal of a priestly caste outraged by a single woman who has stolen their secrets is related as a matter of course. Atlantis the nation is mourned, but the people merit not even a second thought.

As I read

The Lost Continent, I kept thinking of authors who might have been influenced by it. A comparatively recent example is Michael Moorcock in his Elric books. Like Melniboné, Atlantis is an amoral dynastic island culture fallen into decadence that evinces a strong disdain for the up-and-coming peoples of the mainland; also, interestingly, the approach to both capitals is rendered difficult, the former by a maze of passages, the latter by the twists and turns of an extremely long, narrow, and high-walled inlet. Possible echoes in other works of fantastic literature abound, Edgar Rice Burroughs's stories being the most obvious example.

So if you like to read, not only the great pulp writers, but what influenced them; if you enjoy a good H. Rider Haggard romance and don't mind a bit of Victorian stodginess; if you want an interesting early imagining of ancient high technology; if you're looking for Bronze Age battles with giant prehistoric beasts – if you're into any of these things, I say, then give

The Lost Continent a try.