I am pleased to announce my return from yet another successful writing retreat. I went as always to my little discovery, an old hotel in a remote village on El Hierro, the smallest and most exclusive of the Canary Islands. Naturally I stayed in my usual room, which the proprietor so kindly calls la habitación del señor Ordoñez, enjoying a glass or two of my favorite local vintage while watching the sun set over the Atlantic Ocean from behind the wrought-iron rail of my balcony each evening. I would tell you the names of the town and the hotel, but that would only cause them to be inundated with tourists, which would be fatal to my writing ethic and self-image.

Actually, that isn't quite true. What I mean is, I didn't go on a writing retreat, and I've never been to the Canary Islands. As a matter of fact, I'm stuck here in the southwest Texas borderlands just like always. However, I have completed a new novel, The King of Nightspore's Crown, the second installment of my ongoing Antellus series. As I revise it, the Hythloday House art director (me) will begin working on a wrap-around cover and interior decorations. We hope to have it ready by late spring, but we'll see.

(If you haven't read it yet, now's your chance to get caught up on the first installment, Dragonfly. Many thanks to those who have purchased a copy! I hope you enjoy it.)

In other authorial news, I've sold a story called "Salt and Sorcery" to Beneath Ceaseless Skies. I think it's very good, but then, I think that of all my stories! Various things went into the mix, including a little C. L. Moore, Fritz Leiber, and Michael Moorcock. As far as I know, it's the first story to combine the narrative preoccupations of Sword and Sorcery with a salty landscape. Perhaps it'll spawn a new subgenre to take a place beside Sword and Sandal, Sword and Planet, Sword and Soul, and the like. Then again, perhaps not. At any rate, it should come out in the as-yet-unspecified-but-not-so-distant future. I hope everyone who reads it likes it.

Tuesday, December 22, 2015

Wednesday, December 9, 2015

Raphael Ordoñez on Art and Hissing Cockroaches

There's an interview about my art and writing up over at greydogtales today. Our attention was first drawn to greydogtales (currently devoted to "weird fiction, weird art and even weirder lurchers") by their William Hope Hodgson festival in October. You can check out the interview here.

And, if you happen to be a visitor from greydogtales, welcome! Please peruse my blog and enjoy all the extremely important and relevant things I've written about art, fantasy, logic, and chickens. Here's a link to my art; my short fiction can be accessed through the sidebar, and you can purchase my novel Dragonfly here.

Monday, November 30, 2015

Fun With Digital Microscopy

Because this is my blog, where no one can stop me from doing whatever I like, I've posted a bunch of pictures taken with my digital microscope. Here are some of the highlights:

See the rest on the microscopy page.

See the rest on the microscopy page.

Thursday, November 19, 2015

Rites of Spring

I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.

Life on earth is divided into three main phases: the Paleozoic Era, the Mesozoic Era, and the Cenozoic Era. The Cenozoic is the most recent, and saw the dominance of mammals and the evolution of man. The Mesozoic is most famous for the dinosaurs.— "Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock"

|

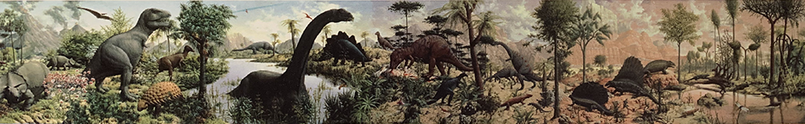

| Rudolph Zallinger's 1947 Age of Reptiles mural at Yale University. I had a copy of this on my bedroom wall when I was a kid. The right-hand part inspires my writing. |

I've also always been drawn to lower life-forms, like mosses and marine invertebrates, which dominated in the Paleozoic.

|

| From Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur. |

|

| An artist's 1906 rendering of a coal swamp with tree ferns, scale trees, and giant scouring rushes. |

|

| Image from Disney's Fantasia (1940). |

|

| Tiffany stained glass window (c. 1890). |

Through the desolate summits swept ranging, intermittent gusts of the terrible antarctic wind; whose cadences sometimes held vague suggestions of a wild and half-sentient musical piping, with notes extending over a wide range, and which for some subconscious mnemonic reason seemed to me disquieting and even dimly terrible. Something about the scene reminded me of the strange and disturbing Asian paintings of Nicholas Roerich, and of the still stranger and more disturbing descriptions of the evilly fabled plateau of Leng which occur in the dreaded Necronomicon of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred.Do you see what we've done? We've made a complete circle: Paleozoic → Chthulu mythos → Nicholas Roerich → The Rite of Spring → Fantasia → Paleozoic.

|

| A member of the Great Race of Yith [source] featured in "The Shadow out of Time." |

|

| One of Roerich's backdrop designs for The Rite of Spring. |

This makes metaphors rather difficult. Can one say that the wall of an ancient crypt is "honeycombed" with tombs, or that an old man is "waspish"? Are airships flown by "aviators"? Are the embarrassed allowed to be "sheepish"? Can the recalcitrant be "cowed" into submission? Is there a "bloom" on a young girl's cheek? Can an oaf make "asinine" comments? Can dawn-tinted clouds wear a "rosy" hue? Do cozening enchanters speak "mellifluously"? Do mighty warriors flex their "muscles"?

Indeed, how far does one go in "winnowing" out words with connotations that violate the rules of the world? As a person who consults an etymological dictionary on a regular basis, I could go crazy fretting about things like this. In the end, I suppose it's all a matter of ear. Whatever you do, the important thing is to not call attention to it. Still, it's worth noting that the great fantasists generally are very careful about word choice.

J. G. Ballard's strange and lovely Drowned World, which I just finished reading, is another literary work featuring the Paleozoic. Though framed as a post-apocalyptic tale, it centers around man's evolutionary regress to a still-present genetic past.

In The Sea Around Us, marine biologist Rachel Carson claims (with what truth I know not) that the chemical composition of human blood represents the salinity of the primordial seas from which our amphibious forebears arose. And zoologist Adolf Portmann discusses in Animal Forms and Patterns how widely differing species share similar embryos, so that the first stages in the development of a man are almost indistinguishable from lower vertebrates and even arthropods. We are still as segmented as millipedes in our backbones.

|

| Trilobites, eurypterids, and horseshoe crabs, from Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur. |

for

yourself, sir, should be old as I am, if like a crab

you could go backward.

— Hamlet

Friday, October 30, 2015

The Tower of Bel in California

In 1991, an engineer by the name of Eugene Tsui designed a building that would have solved all of San Francisco's current housing shortage problems: the Ultima, a mega-tower one mile wide and two miles high, with enough room for one million residents.

Tsui based his design on African termite mounds:

If you've read my novel Dragonfly (and if you haven't then I hope you will), it will be plain why Mr. Tsui's proposal interests and amuses me. But let's hear it from the draft of its sequel, The King of Nightspore's Crown, in which Keftu makes his first attempt to enter the Tower of Bel:

Of course, the Ultima was designed before the Tower of Bel, but I didn't know of it. Believe it or not, I even based my design on termite mounds! (The biota of Antellus are Paleozoic, so hymenopteran social insects such as ants, bees, and wasps are off-limits. So are grass, flowers, milk products, butterflies, bread, and wine.) It's kind of scary when life imitates art...

Tsui based his design on African termite mounds:

The structure is designed to consist of 120 levels, each with its own mini-ecosystem featuring lakes, skies, hills, and rivers. In place of an air conditioning system, aerodynamic windows would help to cool the interior. Just as water from the bottom of an African termite mound cools the rest of the structure, waterfalls on the lower levels—and a giant surrounding lake—would also provide natural air conditioning (cool air rises and is warmed by bodily activity on the upper levels). And a series of mirrors at the building’s core would reflect sunlight throughout. [source]You can check out the stats here. Imagine, only $150 billion! That's just $150,000 per resident – not bad on the Bay Area real estate market. Unfortunately, the residents of San Francisco remained unconvinced:

"San Francisco has this prejudicial view of what architecture ought to be, and it's a very backward and provincial view," Tssui says. "There's a very strange, discriminatory prejudice for retaining that ancient model of San Francisco [at the turn of the century]. It’s been a huge challenge to defy that, and I've had nothing but troubles trying to create something innovative and meaningful and purposeful." [source]Tell me about it, Eugene: nothing makes me think of the words "backward," "provincial," and "discriminatory prejudice" like San Francisco.

If you've read my novel Dragonfly (and if you haven't then I hope you will), it will be plain why Mr. Tsui's proposal interests and amuses me. But let's hear it from the draft of its sequel, The King of Nightspore's Crown, in which Keftu makes his first attempt to enter the Tower of Bel:

The sun climbed to the meridian, and land was out of sight; the sun declined before my face, and darkness mantled the earth. The daystar pursued its appointed course and rose in the east again. The earth was a watery ball, the viaduct a thread stretched across its face, a path from infinity to infinity.

And then at last like a faraway giant it strode through the waves, a faded pillar against the gray-gold bowl of the sky, the axle of the ocean-wide wheel, linked to the rim-city by iron spokes. It marched toward me as the white-hot sun sank again to the sea.

No longer was I a voyeur peeping through a picture-viewer's lenses. It was there before me, the city's crown and pinnacle, the center toward which all men strained, the font from which all culture flowed. From the sea-floor to the stratosphere it rose, its weight upheld by girders that stood on the abyssal plain. Above the waves its shape was like an irregular, many-sided pyramid whose slanting faces became ever steeper as they narrowed, curving upward rather than converging upon an apex, forming a pillar like a tapering prism which, from a distance, looked like a sharp spike set to goad heaven itself.

Its smooth gray sides were gradually resolved into a mosaic of windows and hangars and terraces. A sunlit corpuscle descended upon its stratospheric crown like a spark of divine inspiration. The viaducts that converged at its broad base were so many slender spider-threads.

The rail-car crossed into the annular belt of floating crops just as the sun began to melt into the horizon. The sea-vegetables were tended by helots, but no helot lived in the Tower. They were brought over from the coasts in weekly shifts.

The belt was miles across, and dusk had fallen before the car gained the inner boundary. The Tower had by that time swollen to occlude the sky, its faces aglitter with silver diamonds, its stratospheric crown yet ablaze with the light of day.

The train was passing over the ring of pleasure gardens now. The paper lanterns were like colored fireflies visiting the floating plats.Like the Ultima, the Tower of Bel is an edifice built to house a city, featuring miniature ecosystems and supplied with piped-in sunlight. Unlike the Ultima, space elevators link the Tower's stratospheric crown with the Hanging Gardens of Narva, a toric space-palace in geostationary orbit. The Tower is located in the middle of the Tethys Sea, with its bulk partly upheld by the force of buoyancy; the ocean provides a natural cooling system, like Mr. Tsui's moat (ahem, lake), but also ensures that the riffraff of the city can be held at arm's length.

Of course, the Ultima was designed before the Tower of Bel, but I didn't know of it. Believe it or not, I even based my design on termite mounds! (The biota of Antellus are Paleozoic, so hymenopteran social insects such as ants, bees, and wasps are off-limits. So are grass, flowers, milk products, butterflies, bread, and wine.) It's kind of scary when life imitates art...

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

Mining the Bible

The Book of Tobit isn't the most well-known book of the Bible. For one thing, it's very short; for another, it's not in all Bibles. Catholics refer to it as "deuterocanonical," indicating that it is not in the current Hebrew Bible, but regard it as canon; to Protestants it is "apocryphal," hence non-canonical.

The events Tobit describes are placed in the 8th century BC, but it was probably written in the 3rd or 2nd century, or at any rate sometime after the return from the exile. It was written in Aramaic, but most modern editions are based on one of several ancient Greek versions. The Aramaic and Hebrew versions were thought lost until fragments were found in Cave IV at Qumran. St. Jerome claimed to have based his version for the Latin Vulgate on an Aramaic copy.

The book is, according to most scholars, a kind of religious fairy tale:

Tobit is a righteous Israelite living in Nineveh after being deported by Shalmaneser, the king of Assyria who conquered the northern kingdom. He adheres to the Mosaic law, practices charity, and is especially solicitous regarding the burial of the dead. This gets him in trouble with Sennacherib, Shalmaneser's successor, forcing him to flee for his life. (There are some historical errors here, but I'm presenting the story as-is.) After Sennacherib's assassination, Tobit's nephew Ahiqar (a Near Eastern folk hero) pulls some strings to allow for his return. He takes up his dead-burying activities again, prompting the derision of his neighbors. After burying a man strangled in the marketplace, he sleeps in the open, and birds poop in his eyes. This causes cataracts and, eventually, blindness. He prays for death.

Meanwhile, a young Israelite woman named Sarah, who lives in Ecbatana in Media (in modern-day Iran), is experiencing troubles of her own. She's gotten married seven times, but every time, just as she was preparing to go to bed with her new husband, the demon Asmodeus (from the Persian aeshma daeva, demon of wrath) appeared and killed the groom to prevent their consummating their union. Her maid accuses her of having strangled them all. She prays for death.

Both prayers are heard by God, who sends the angel Raphael to make things right.

Tobit sends his son Tobias to Media to retrieve a large sum of money he deposited there many years ago. Tobias enlists the service of a young man (Raphael in mortal disguise) who claims to know the roads. While en route, a fish tries to eat Tobiah's foot as he's bathing in the Tigris River. He catches the fish, and Raphael advises him to keep the liver, the heart, and the gall. The first two repel demons when roasted, and the third is a cure for cataracts.

They reach Sarah's house. Tobiah marries Sarah and they go to the bridal chamber. He places the liver and heart on embers prepared for incense. Asmodeus is driven by the smoke into Upper Egypt, where he is bound by Raphael. Tobiah and Sarah rise to say a prayer together. It's a prayer of thanksgiving that goes from the cosmic to the intimate, dwelling on the heavens and the earth, Adam and Eve, sexual complementarity, mutual support, sincere love, and the hope of growing old together.

Sarah says, "Amen," and they get in bed together. Sarah's father, who had ordered a grave to be dug in the night, has it filled in when he discovers the happy outcome. The money is retrieved and the couple goes to Nineveh. Tobiah applies the gall to his father's eyes and is able to peel the cataracts off his eyeballs. The angel then reveals his true identity:

All in all, it's a strange, beautiful tale full of bizarre happenings and vivid details that passes freely and unapologetically from the scatological, the visceral, and the sexual to the angelic and the divine. It's entertaining – it could almost be the basis for a story in the Arabian Nights – at the same time as being edifying and thought-provoking. More than anything, viewed purely as a story, it's a wonderful mine for writers.

John O'Neill of Black Gate fame recently mentioned his surprise that fantasy authors don't do more with Biblical material:

The truth is, the Bible has a lot of weird, sexy, and violent parts that don't come up in Sunday school. The Old Testament is a Bronze-Age epic of love and revenge and worship and war, rich in historical detail and local color, with poetic images that are some of the most beautiful in any language. It's a bridge from the cosmic to the historical, establishing a supernatural link and parallel between the Temple liturgy and the creation of the universe.

Even the New Testament has more strangeness to mine than most people suspect. Think, for instance, of the exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac, in which Jesus casts the demon called Legion ("for we are many") out of a tomb-dwelling demoniac, but, at its request, allows it to enter a herd of swine, which promptly drown themselves in the sea. That story alone prompts countless questions about the nature of the world of spirits; it makes you feel like you're catching just a glimpse into a strange and frightening plane with its own secret laws.

One fantasy author who did do a lot with Biblical material is Madeleine L'Engle. I read her Time Quartet many times when I was a pre-teen. My favorite was Many Waters, in which the "normal" Murray twins Dennys and Sandy are accidentally time-warped into the days leading up to the Deluge, where they meet the patriarchs, fall in love with a beautiful young woman, and come into contact with nephilim, seraphim, virtual unicorns, and tiny wooly mammoths. When I was in the fourth grade I began a project of reading the King James Version of the Bible, and Many Waters went hand-in-hand with the strange things I was encountering there. I even dressed as Japheth for Book Day in the fifth grade.

I happen to do a lot with Biblical material myself. The world of Antellus represents a blend of Greek and Semitic mythology. Like L'Engle, I'm especially drawn to the first part of Genesis, from the creation accounts (there's two of them, you know) down to the Tower of Babel. Robert Alter's Genesis: Translation and Commentary (W. W. Norton) is an excellent non-religious translation. I'm also fascinated by the mythologies of other Semitic peoples, especially the Arabian/Islamic jinn, on which I base my nephelim, as well as some of the other ancient Jewish traditions. But I have a special affection for Tobit, which is one reason I chose my pen name as I did.

So, go read your Bible. If you don't have one, get one. I'm sure you can find someone more than willing to give you a nice one for free, even if you tell them that you just want to mine it for material. It just might not have the deuterocanonical books in it...

The events Tobit describes are placed in the 8th century BC, but it was probably written in the 3rd or 2nd century, or at any rate sometime after the return from the exile. It was written in Aramaic, but most modern editions are based on one of several ancient Greek versions. The Aramaic and Hebrew versions were thought lost until fragments were found in Cave IV at Qumran. St. Jerome claimed to have based his version for the Latin Vulgate on an Aramaic copy.

The book is, according to most scholars, a kind of religious fairy tale:

Tobit is a righteous Israelite living in Nineveh after being deported by Shalmaneser, the king of Assyria who conquered the northern kingdom. He adheres to the Mosaic law, practices charity, and is especially solicitous regarding the burial of the dead. This gets him in trouble with Sennacherib, Shalmaneser's successor, forcing him to flee for his life. (There are some historical errors here, but I'm presenting the story as-is.) After Sennacherib's assassination, Tobit's nephew Ahiqar (a Near Eastern folk hero) pulls some strings to allow for his return. He takes up his dead-burying activities again, prompting the derision of his neighbors. After burying a man strangled in the marketplace, he sleeps in the open, and birds poop in his eyes. This causes cataracts and, eventually, blindness. He prays for death.

Meanwhile, a young Israelite woman named Sarah, who lives in Ecbatana in Media (in modern-day Iran), is experiencing troubles of her own. She's gotten married seven times, but every time, just as she was preparing to go to bed with her new husband, the demon Asmodeus (from the Persian aeshma daeva, demon of wrath) appeared and killed the groom to prevent their consummating their union. Her maid accuses her of having strangled them all. She prays for death.

Both prayers are heard by God, who sends the angel Raphael to make things right.

Tobit sends his son Tobias to Media to retrieve a large sum of money he deposited there many years ago. Tobias enlists the service of a young man (Raphael in mortal disguise) who claims to know the roads. While en route, a fish tries to eat Tobiah's foot as he's bathing in the Tigris River. He catches the fish, and Raphael advises him to keep the liver, the heart, and the gall. The first two repel demons when roasted, and the third is a cure for cataracts.

They reach Sarah's house. Tobiah marries Sarah and they go to the bridal chamber. He places the liver and heart on embers prepared for incense. Asmodeus is driven by the smoke into Upper Egypt, where he is bound by Raphael. Tobiah and Sarah rise to say a prayer together. It's a prayer of thanksgiving that goes from the cosmic to the intimate, dwelling on the heavens and the earth, Adam and Eve, sexual complementarity, mutual support, sincere love, and the hope of growing old together.

Sarah says, "Amen," and they get in bed together. Sarah's father, who had ordered a grave to be dug in the night, has it filled in when he discovers the happy outcome. The money is retrieved and the couple goes to Nineveh. Tobiah applies the gall to his father's eyes and is able to peel the cataracts off his eyeballs. The angel then reveals his true identity:

I am Raphael, one of the seven holy angels who present the prayers of the saints and enter into the presence of the glory of the Holy One.He also gives some insight into the nature of his supposed corporeality:

All these days I merely appeared to you and did not eat or drink, but you were seeing a vision.Years later, from his deathbed, Tobit admonishes his son to return to Ecbatana, for the prophet has preached the destruction of Nineveh. So Tobiah and Sarah and their family return to Media, where they hear about the fall of Nineveh and praise God.

All in all, it's a strange, beautiful tale full of bizarre happenings and vivid details that passes freely and unapologetically from the scatological, the visceral, and the sexual to the angelic and the divine. It's entertaining – it could almost be the basis for a story in the Arabian Nights – at the same time as being edifying and thought-provoking. More than anything, viewed purely as a story, it's a wonderful mine for writers.

John O'Neill of Black Gate fame recently mentioned his surprise that fantasy authors don't do more with Biblical material:

When I was editing fiction for Black Gate, I was always a little surprised at how many writers were eager to tap the dead religions of Ancient Greece, Rome and Scandinavia, and how few seemed interested in the rich storytelling of the Bible. Maybe it was an overabundance of respect — or, more likely, a lack of real familiarity with the source material.I suspect that, culturally speaking, it's just too close, for believers as well as non-believers. There's a sense of ownership. We know the Bible, or so we think. It's old hat.

The truth is, the Bible has a lot of weird, sexy, and violent parts that don't come up in Sunday school. The Old Testament is a Bronze-Age epic of love and revenge and worship and war, rich in historical detail and local color, with poetic images that are some of the most beautiful in any language. It's a bridge from the cosmic to the historical, establishing a supernatural link and parallel between the Temple liturgy and the creation of the universe.

Even the New Testament has more strangeness to mine than most people suspect. Think, for instance, of the exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac, in which Jesus casts the demon called Legion ("for we are many") out of a tomb-dwelling demoniac, but, at its request, allows it to enter a herd of swine, which promptly drown themselves in the sea. That story alone prompts countless questions about the nature of the world of spirits; it makes you feel like you're catching just a glimpse into a strange and frightening plane with its own secret laws.

One fantasy author who did do a lot with Biblical material is Madeleine L'Engle. I read her Time Quartet many times when I was a pre-teen. My favorite was Many Waters, in which the "normal" Murray twins Dennys and Sandy are accidentally time-warped into the days leading up to the Deluge, where they meet the patriarchs, fall in love with a beautiful young woman, and come into contact with nephilim, seraphim, virtual unicorns, and tiny wooly mammoths. When I was in the fourth grade I began a project of reading the King James Version of the Bible, and Many Waters went hand-in-hand with the strange things I was encountering there. I even dressed as Japheth for Book Day in the fifth grade.

I happen to do a lot with Biblical material myself. The world of Antellus represents a blend of Greek and Semitic mythology. Like L'Engle, I'm especially drawn to the first part of Genesis, from the creation accounts (there's two of them, you know) down to the Tower of Babel. Robert Alter's Genesis: Translation and Commentary (W. W. Norton) is an excellent non-religious translation. I'm also fascinated by the mythologies of other Semitic peoples, especially the Arabian/Islamic jinn, on which I base my nephelim, as well as some of the other ancient Jewish traditions. But I have a special affection for Tobit, which is one reason I chose my pen name as I did.

So, go read your Bible. If you don't have one, get one. I'm sure you can find someone more than willing to give you a nice one for free, even if you tell them that you just want to mine it for material. It just might not have the deuterocanonical books in it...

Saturday, October 24, 2015

William Hope Hodgson Festival

I have been apprised of a William Hope Hodgson festival going on during the month of October at the website greydogtales.com of author John Linwood Grant. Hodgson is constant source of inspiration to me, as I've mentioned in the past, and it's always encouraging to see WHH-related activity going on around the Internet. Mr. Grant's website is (partially) dedicated to longdogs, which, irrelevantly speaking, are something like how I imagine the Night Hound. He's in the middle of posting a eclectic mix of Hodgsoniana, including several interviews with well-known authors influenced by Hodgson, and I recommend you take a look. While you're there, be sure to check out the gallery of WHH cover art.

Here is my own contribution to the festivities: Robert LoGrippo's wraparound cover art from the Ballantine Adult Fantasy edition of The Boats of the "Glen Carrig":

Scanned from my own copy. Lovely, isn't it? While not particularly evocative of the story in its details, it captures the general mood of weird horror on the high seas.

Here is my own contribution to the festivities: Robert LoGrippo's wraparound cover art from the Ballantine Adult Fantasy edition of The Boats of the "Glen Carrig":

Scanned from my own copy. Lovely, isn't it? While not particularly evocative of the story in its details, it captures the general mood of weird horror on the high seas.

Monday, October 19, 2015

Crimson Peak

Feeling prodigal and carefree with the proceeds of my recent art show, I decided to take in some fine cinema yesterday at the local theater. Actually, the Sunday matinee here costs all of $4.00, somewhat more than I make from the sale of a copy of my book, so I'm naturally selective when it comes to spending my hard-earned cash. But Guillermo del Toro's Crimson Peak opened this weekend, and I've so enjoyed most everything I've seen by him that I couldn't possibly stay away.

Though it contains elements of horror, Crimson Peak is in fact a gothic romance, which is a genre of its own with a long history and well-established tropes. The seminal work is said to be Horace Walpole's 1764 The Castle of Otranto, subtitled (in later editions) A Gothic Story, but perhaps "Bluebeard" is the basic template for the specific type of story in question. At any rate, gothic romance or (more broadly speaking) gothic fiction became widely popular through the nineteenth century. Some of the most well-known English novels from the period, like Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre, have elements of gothic romance, and Jane Austen parodied the genre in Northanger Abbey.

Today the term is used to describe a subgenre of the twentieth-century romance novel owing to this tradition, by authors such as Daphne du Maurier or Mary Stewart. I read some of the latter many years ago, having found them among my mother's books, but don't recall the titles or authors. According to my vague memories, the plots invariably involve a lady who marries into a decadent old family with a large, creepy house and a few (literal) skeletons in the (secret) closet, generally of the former-wife variety. Of course I was there for the secret passages and skeletons.

So the appearance of a film like Crimson Peak is something of a phenomenon. It's a beautifully faithful cinematic adaptation of a literary genre that's (now) almost as storied and neglected as the houses that feature so prominently in its exemplars. It has a spirited young heroine, a brooding, titled scion of a decadent family, a horrifically decayed old house with paintings hung in salon style and interior décor so spiky and gothic it's almost perverse, and a dollop of intra-familial feminine animosity.

Oh, and blood. Lots and lots of blood. The whole movie is drenched in blood.

The film also involves a certain number of ghosts. It begins and ends with ghosts. These ghosts are as scary as hell. Some people might therefore be led to believe that it's a ghost story. But the ghosts are only a metaphor, you see. Amusingly, that assertion is one the heroine, a budding novelist, makes of her own manuscript. Crimson Peak is, to a certain extent, a commentary on its own genre. "Bluebeard" is never far off, but there's a twist.

The visuals are, of course, stunning, and equal to anything in Pan's Labyrinth, which is probably del Toro's best work to date. Allerdale Hall is the most gorgeous, most decadent haunted house I've ever seen on the screen. The movie ticket is more than worth the price just for that. The ghosts are, as I said, delightfully monstrous. They emerge like slow spiders from the inky blackness that seems always threatening to engulf the protagonist.

Insects and clockwork form important motifs, as they do in practically all of del Toro's films from Cronos on. Crimson Peak features some lovely, horrific images of butterflies being devoured by ants; huge, grotesque moths inhabit the old house. There are plenty of wind-up gizmos and steam-powered machines as well, including a creepy elevator that takes you down to the basement you're not supposed to go down to.

No spoilers here, but, familiar as I am with the genre, I guessed all the secrets in the first ten minutes. That didn't lessen the enjoyment, because I don't really watch movies or read stories like this out of a desire to see the mystery solved. I've avoided any and all reviews, as I do whenever I plan on reviewing a movie myself, but I have seen that Crimson Peak hasn't done as well as hoped. I can guess why: people go expecting horror, and instead get gothic romance, which is its own thing. And Crimson Peak really is a romance. That is to say, it's structured as a love story, and its eroticism is (how shall I put this?) female-centric, with a focus on emotion rather than skin. You might almost call it a chick flick, though the various brutally graphic skull bashings and splittings tip the scales a little bit the other way. So it's a blood-soaked horror-romance, which kind of seems like a tough sell.

But it's lovely, I tell you, simply lovely. Please go see this film. If you do, maybe your ticket will be the one to convince the studio to let del Toro make that At the Mountains of Madness movie he's wanted to do for years.

Though it contains elements of horror, Crimson Peak is in fact a gothic romance, which is a genre of its own with a long history and well-established tropes. The seminal work is said to be Horace Walpole's 1764 The Castle of Otranto, subtitled (in later editions) A Gothic Story, but perhaps "Bluebeard" is the basic template for the specific type of story in question. At any rate, gothic romance or (more broadly speaking) gothic fiction became widely popular through the nineteenth century. Some of the most well-known English novels from the period, like Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre, have elements of gothic romance, and Jane Austen parodied the genre in Northanger Abbey.

Today the term is used to describe a subgenre of the twentieth-century romance novel owing to this tradition, by authors such as Daphne du Maurier or Mary Stewart. I read some of the latter many years ago, having found them among my mother's books, but don't recall the titles or authors. According to my vague memories, the plots invariably involve a lady who marries into a decadent old family with a large, creepy house and a few (literal) skeletons in the (secret) closet, generally of the former-wife variety. Of course I was there for the secret passages and skeletons.

So the appearance of a film like Crimson Peak is something of a phenomenon. It's a beautifully faithful cinematic adaptation of a literary genre that's (now) almost as storied and neglected as the houses that feature so prominently in its exemplars. It has a spirited young heroine, a brooding, titled scion of a decadent family, a horrifically decayed old house with paintings hung in salon style and interior décor so spiky and gothic it's almost perverse, and a dollop of intra-familial feminine animosity.

Oh, and blood. Lots and lots of blood. The whole movie is drenched in blood.

The film also involves a certain number of ghosts. It begins and ends with ghosts. These ghosts are as scary as hell. Some people might therefore be led to believe that it's a ghost story. But the ghosts are only a metaphor, you see. Amusingly, that assertion is one the heroine, a budding novelist, makes of her own manuscript. Crimson Peak is, to a certain extent, a commentary on its own genre. "Bluebeard" is never far off, but there's a twist.

The visuals are, of course, stunning, and equal to anything in Pan's Labyrinth, which is probably del Toro's best work to date. Allerdale Hall is the most gorgeous, most decadent haunted house I've ever seen on the screen. The movie ticket is more than worth the price just for that. The ghosts are, as I said, delightfully monstrous. They emerge like slow spiders from the inky blackness that seems always threatening to engulf the protagonist.

Insects and clockwork form important motifs, as they do in practically all of del Toro's films from Cronos on. Crimson Peak features some lovely, horrific images of butterflies being devoured by ants; huge, grotesque moths inhabit the old house. There are plenty of wind-up gizmos and steam-powered machines as well, including a creepy elevator that takes you down to the basement you're not supposed to go down to.

No spoilers here, but, familiar as I am with the genre, I guessed all the secrets in the first ten minutes. That didn't lessen the enjoyment, because I don't really watch movies or read stories like this out of a desire to see the mystery solved. I've avoided any and all reviews, as I do whenever I plan on reviewing a movie myself, but I have seen that Crimson Peak hasn't done as well as hoped. I can guess why: people go expecting horror, and instead get gothic romance, which is its own thing. And Crimson Peak really is a romance. That is to say, it's structured as a love story, and its eroticism is (how shall I put this?) female-centric, with a focus on emotion rather than skin. You might almost call it a chick flick, though the various brutally graphic skull bashings and splittings tip the scales a little bit the other way. So it's a blood-soaked horror-romance, which kind of seems like a tough sell.

But it's lovely, I tell you, simply lovely. Please go see this film. If you do, maybe your ticket will be the one to convince the studio to let del Toro make that At the Mountains of Madness movie he's wanted to do for years.

Thursday, October 15, 2015

Fantasy in Film Part Two

A while back I wrote a couple of posts complaining about the lack of fantasy in film. As I noted then, there are lots of fantasy films in a generic or material sense. Some of them (e.g., Conan the Barbarian) are among my favorite movies. The problem is that they fail to convey the sense of myth, of mystery, of otherworldliness, that I'm always looking for. To see what I mean, think of Fantasy as Tolkien describes it in "On Fairy Stories," translated into film.

The best good example I could come up with at the time, The Night of the Hunter, technically isn't fantasy at all. It comes close, though, in that it translates tales like Hansel and Gretel and The Juniper Tree into an American idiom. It's gothic masterpiece, by turns beautiful and terrifying.

My search has since led me to two more examples of good fairy tale movies.

The first is La Belle et la Bête (1946), a French adaptation of the traditional tale of Beauty and the Beast (most famously novelized by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont in 1756) directed by the great Jean Cocteau. What a beautiful, bizarre, unsettling film this is!

Its plot hews fairly closely to the original story, though introducing a ne'er-do-well brother and his freeloading friend, who also happens to be Belle's failed suitor. Everyone knows how the tale itself goes, so I'll not comment on that directly.

What makes this movie magical is the style: the sets, the acting, the camera work. The Beast's castle is alive, with candelabras that are living arms, and hearth ornaments that watch you as you move about the room. There's an overpowering sense of claustrophobia and decay: the rooms are broodingly dark and stuffy, the gardens are overgrown, and everything is over-decorated and run down. It gives me the same feeling that certain nightmares give me, vaguely unsettling rather than frightening. Cocteau has been called a Surrealist filmmaker and, though I think he denied the connection, there is a strong element of surrealism in this film. The image of ants crawling in and out of a man's hand is not far away here. At many points I was also reminded of Gustave Doré.

The Beast himself is well portrayed. The actor is Jean Marais (shown below), who also plays the friend as well as the Prince into whom the Beast transforms. He also happened to be Cocteau's lover. This leads us to the film's subtext, which is very strange, and something I'm not sure I understand. Of course, it may be that I'm just misinterpreting the emotional framework. To explain, I'll have to discuss the ending, so I suppose I should issue a spoiler alert.

Toward the end, as the Beast lies dying of his hitherto-unrequited love for Belle, the brother and friend sneak onto the Beast's castle grounds and try to break into a treasure-house called Diana's Pavilion, which (we've been told) houses the Beast's true riches. As the friend attempts to climb through the glass roof, a statue of the goddess comes to life and shoots him with an arrow. He drops into the chamber, transforming into the Beast.

The Beast becomes a handsome Prince at the same instant. He's a pretty popinjay, with golden hair, poofy pantaloons, and tights. He glibly explains what had transformed him into a Beast. He's flip. He's chatty. He's annoying. He's the precise antithesis of his tragic and brooding former self.

The Beast becomes a handsome Prince at the same instant. He's a pretty popinjay, with golden hair, poofy pantaloons, and tights. He glibly explains what had transformed him into a Beast. He's flip. He's chatty. He's annoying. He's the precise antithesis of his tragic and brooding former self.

The look on Belle's face is priceless, a mixture of pleasure, surprise, and (perhaps) dismay – it's plain that she doesn't exactly know what to make of him. Is she disappointed that the Beast she has come to love has been replaced by this chattering doll? The Prince embraces her. They fly up into the sky to return to his kingdom, and that's the end.

So what exactly is going on here? At first the ending really bothered me, but on reflection it seems like something is going on under the surface. The film is just too conscious of what it's doing for it to be an accident. There's a sense I get when I think about the most powerful fairy tales, myths, and stories, that it isn't good to dissect things too much. They have mystery rather than meaning, in the sense that there is something there, something subconscious that can't be reduced to words or concepts. That's how this movie makes me feel, so perhaps I'll stop there.

At any rate, it's apparent that this film has influenced many things; Ridley Scott's Blade Runner and Legend and Francis Ford Coppola's Dracula spring to mind. (Come to think of it, both Legend and Bram Stoker's Dracula are decent examples of fantasy in film. I haven't seen either in a very long time, so perhaps I'll have to revisit them soon.)

The second movie I'd like to discuss is Guillermo del Toro's El Laberinto del Fauno (2006), known in English as Pan's Labyrinth.

Del Toro is a director I've been coming more and more to appreciate; I've watched a number of his works from various phases in his career, e.g., Cronos, Blade II, the Hellboy movies, and Pacific Rim. Though ranging from low-budget horror to art films to popcorn fare, his movies exhibit certain common themes, as well as an obsessive precision and explicitness and a preoccupation with clockwork and insects. For years he's been wanting to do an At the Mountains of Madness adaptation, which, because of our sins, continues to be put off. His gothic romance Crimson Peak is coming soon, and I'm very excited about it.

Most of del Toro's works are tinged with some horror, and Pan's Labyrinth is certainly no exception. It features what may be the most terrifying monster ever to appear on screen: the infamous Pale Man. The monsters and other creatures are largely done with make-up and animatronics, heightening the realism and very real terror.

After a mythic prelude, the story unfolds against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War, in the forests and mountains of the northwest. The protagonist is a little girl named Ofelia, the stepdaughter of a brutal, psychotic Francoist military commander, Captain Vidal. Ofelia and her pregnant mother have come to stay at the outpost because Vidal wants his wife by his side when she gives birth. There are really two parallel story lines, one centered on Ofelia and her soon-to-be-born baby brother, the other on Mercedes, Vidal's housekeeper, a spy for rebel guerillas in the area (one of whom is her brother).

Ofelia encounters a friendly but sinister faun in the ancient labyrinth behind the outpost. The faun informs her that she is really the princess of a magical kingdom, and gives her three tasks to complete before she can return to the land of her birth. The film leaves open the possibility that all of her experiences are dreams or hallucinations. At one point she is even dressed as Alice, whose adventures took place in a dream. And, after all, she is named after a mad girl who drowned herself. The ending suggests that her return to the kingdom is only a vision that passes before her eyes as she dies. But of course it's all real; why would I watch a movie about a little girl hallucinating and then dying?

Incidentally, despite the Spanish language and location, the movie made me think more of English fairy tales and literature than (say) magic realism, what with the Celtic artifacts, the references to Lewis Carroll and Shakespeare, and so on. Of course Goya's Black Paintings and Disasters of War are never far away, either.

Pan's Labyrinth is a dark and beautiful masterpiece, a terrifying fairy tale brought to life. Both these films make you remember that a true fairy tale is a story that begins in the prosaic and ends in the unbounded wonders and horrors of the irrational subconscious.

The best good example I could come up with at the time, The Night of the Hunter, technically isn't fantasy at all. It comes close, though, in that it translates tales like Hansel and Gretel and The Juniper Tree into an American idiom. It's gothic masterpiece, by turns beautiful and terrifying.

My search has since led me to two more examples of good fairy tale movies.

The first is La Belle et la Bête (1946), a French adaptation of the traditional tale of Beauty and the Beast (most famously novelized by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont in 1756) directed by the great Jean Cocteau. What a beautiful, bizarre, unsettling film this is!

Its plot hews fairly closely to the original story, though introducing a ne'er-do-well brother and his freeloading friend, who also happens to be Belle's failed suitor. Everyone knows how the tale itself goes, so I'll not comment on that directly.

What makes this movie magical is the style: the sets, the acting, the camera work. The Beast's castle is alive, with candelabras that are living arms, and hearth ornaments that watch you as you move about the room. There's an overpowering sense of claustrophobia and decay: the rooms are broodingly dark and stuffy, the gardens are overgrown, and everything is over-decorated and run down. It gives me the same feeling that certain nightmares give me, vaguely unsettling rather than frightening. Cocteau has been called a Surrealist filmmaker and, though I think he denied the connection, there is a strong element of surrealism in this film. The image of ants crawling in and out of a man's hand is not far away here. At many points I was also reminded of Gustave Doré.

The Beast himself is well portrayed. The actor is Jean Marais (shown below), who also plays the friend as well as the Prince into whom the Beast transforms. He also happened to be Cocteau's lover. This leads us to the film's subtext, which is very strange, and something I'm not sure I understand. Of course, it may be that I'm just misinterpreting the emotional framework. To explain, I'll have to discuss the ending, so I suppose I should issue a spoiler alert.

Toward the end, as the Beast lies dying of his hitherto-unrequited love for Belle, the brother and friend sneak onto the Beast's castle grounds and try to break into a treasure-house called Diana's Pavilion, which (we've been told) houses the Beast's true riches. As the friend attempts to climb through the glass roof, a statue of the goddess comes to life and shoots him with an arrow. He drops into the chamber, transforming into the Beast.

The Beast becomes a handsome Prince at the same instant. He's a pretty popinjay, with golden hair, poofy pantaloons, and tights. He glibly explains what had transformed him into a Beast. He's flip. He's chatty. He's annoying. He's the precise antithesis of his tragic and brooding former self.

The Beast becomes a handsome Prince at the same instant. He's a pretty popinjay, with golden hair, poofy pantaloons, and tights. He glibly explains what had transformed him into a Beast. He's flip. He's chatty. He's annoying. He's the precise antithesis of his tragic and brooding former self.The look on Belle's face is priceless, a mixture of pleasure, surprise, and (perhaps) dismay – it's plain that she doesn't exactly know what to make of him. Is she disappointed that the Beast she has come to love has been replaced by this chattering doll? The Prince embraces her. They fly up into the sky to return to his kingdom, and that's the end.

So what exactly is going on here? At first the ending really bothered me, but on reflection it seems like something is going on under the surface. The film is just too conscious of what it's doing for it to be an accident. There's a sense I get when I think about the most powerful fairy tales, myths, and stories, that it isn't good to dissect things too much. They have mystery rather than meaning, in the sense that there is something there, something subconscious that can't be reduced to words or concepts. That's how this movie makes me feel, so perhaps I'll stop there.

At any rate, it's apparent that this film has influenced many things; Ridley Scott's Blade Runner and Legend and Francis Ford Coppola's Dracula spring to mind. (Come to think of it, both Legend and Bram Stoker's Dracula are decent examples of fantasy in film. I haven't seen either in a very long time, so perhaps I'll have to revisit them soon.)

The second movie I'd like to discuss is Guillermo del Toro's El Laberinto del Fauno (2006), known in English as Pan's Labyrinth.

Del Toro is a director I've been coming more and more to appreciate; I've watched a number of his works from various phases in his career, e.g., Cronos, Blade II, the Hellboy movies, and Pacific Rim. Though ranging from low-budget horror to art films to popcorn fare, his movies exhibit certain common themes, as well as an obsessive precision and explicitness and a preoccupation with clockwork and insects. For years he's been wanting to do an At the Mountains of Madness adaptation, which, because of our sins, continues to be put off. His gothic romance Crimson Peak is coming soon, and I'm very excited about it.

Most of del Toro's works are tinged with some horror, and Pan's Labyrinth is certainly no exception. It features what may be the most terrifying monster ever to appear on screen: the infamous Pale Man. The monsters and other creatures are largely done with make-up and animatronics, heightening the realism and very real terror.

After a mythic prelude, the story unfolds against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War, in the forests and mountains of the northwest. The protagonist is a little girl named Ofelia, the stepdaughter of a brutal, psychotic Francoist military commander, Captain Vidal. Ofelia and her pregnant mother have come to stay at the outpost because Vidal wants his wife by his side when she gives birth. There are really two parallel story lines, one centered on Ofelia and her soon-to-be-born baby brother, the other on Mercedes, Vidal's housekeeper, a spy for rebel guerillas in the area (one of whom is her brother).

Ofelia encounters a friendly but sinister faun in the ancient labyrinth behind the outpost. The faun informs her that she is really the princess of a magical kingdom, and gives her three tasks to complete before she can return to the land of her birth. The film leaves open the possibility that all of her experiences are dreams or hallucinations. At one point she is even dressed as Alice, whose adventures took place in a dream. And, after all, she is named after a mad girl who drowned herself. The ending suggests that her return to the kingdom is only a vision that passes before her eyes as she dies. But of course it's all real; why would I watch a movie about a little girl hallucinating and then dying?

Incidentally, despite the Spanish language and location, the movie made me think more of English fairy tales and literature than (say) magic realism, what with the Celtic artifacts, the references to Lewis Carroll and Shakespeare, and so on. Of course Goya's Black Paintings and Disasters of War are never far away, either.

Pan's Labyrinth is a dark and beautiful masterpiece, a terrifying fairy tale brought to life. Both these films make you remember that a true fairy tale is a story that begins in the prosaic and ends in the unbounded wonders and horrors of the irrational subconscious.

Friday, October 2, 2015

The Apeinator

Last year I began a project of watching sci-fi films from the seventies. I was born in the seventies but grew up in the eighties, so I haven't seen much before The Terminator or Escape from New York. Alien and Star Wars are notable exceptions, but I think of those as belonging more to the eighties, given their multiple sequels, and the fact that I watched them when I was a kid.

Anyway, here's a summary of what I've gotten through so far:

- Planet of the Apes (1968): Not from the seventies but goes with the others.

- The Omega Man (1971): Very cool and slightly funky.

- Silent Running (1972): Underdeveloped tree-hugger flick featuring an overwrought, lachrymose protagonist who flies through space in a terrycloth bathrobe-habit and cuddles bunnies to the tune of throaty Joan Baez ballads. Weird.

- Soylent Green (1973): Surprisingly excellent future noir with three legendary actors who played in major noir films; this is Edward G. Robinson's swan song, with a beautifully intimate farewell between his character and Charlton Heston's that goes beyond mere acting.

- Westworld (1973): Never trust robots. Especially creepy Yul Brynner robots.

- Death Race 2000 (1975): How about I just not review this one? For me the high point was the fistfight between David Carradine and Sylvester Stallone. Never knew such a thing existed.

- Logan's Run (1976): Evocative, strangely beautiful, and life-affirming.

- The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976): Good Lord, what did I just watch? (Actually I kind of liked this one.)

(For my reflections on the recent reboot films and how they stack up against Planet of the Apes, see here; for my review of the original Pierre Boulle novel, see here.)

Damn Dirty Apes Movies

One thing you notice if you watch the original Apes movies through from beginning to end (which my father claims to have done in one night at a drive-in theater) is that they're quite inconsistent in their world-building. Heck, the first installment isn't even consistent with itself. For instance, it draws attention to the absence of a moon, a detail that's never explained, despite the fact that the planet turns out to be earth. (Oops, spoiler alert.) No explanation as to how the astronauts got back to earth instead of the planet they were making for is given, either.

One minor aspect of the world-building in Planet that I particularly appreciate is the fact that there are no birds. This is important, because the apes disbelieve Taylor's story of having come from the sky. If they had seen birds, the paper airplane folded by Taylor wouldn't have been remarkable to them. But, again, no particular attention is drawn to the fact. A less sensitive, more heavy-handed approach would have underscored it too much, or else ignored the issue altogether.

I mention this subtlety because it does seem purposeful to me, and because the second installment, Beneath the Planet of the Apes, blithely abandons it without an afterthought. That's typical of the series: what was a major plot point in one installment might be completely ignored in the next.

Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970)

If I were to rank the Apes movies from first to fifth, this would come in fourth (right before the execrable Battle). After a brief opening featuring Taylor (Charlton Heston again), his mute lover Nova, and some embarrassing special effects, the narrative shifts to his fellow astronaut Brent, who has come in search of him, which, for the record, makes absolutely no sense. Brent believes initially that he's on another planet, but, stunningly, discovers that it's actually a far-future earth ruled by apes! Actually, it's not stunning at all, as this is exactly the same plot as the first installment, only much less artfully executed.

As a matter of fact, the actor who plays Brent (James Franciscus) seems to have a Charlton Heston thing going on. It's almost as though they told him, look, just act like him, OK? Unable to get Heston for the whole film, they compromised by hiring a cheap knock-off for the non-Heston scenes. There's actually one part that seems lifted from Ben-Hur, hand gestures and all. Weird.

Toward the end Brent discovers the buried remains of NYC which is ruled by a race of mutant telepathic humans who worship an atomic bomb using a vernacular translation of the mass. So I guess that's a new twist. The sets are pretty cool, I have to say. Brent is captured by the mutants and finds Taylor. The mutants force the two to fight. I kept hoping Taylor would just kill Brent. That would have made up for a lot. Think about it: throughout the movie, Brent's like this irritating, phony, less muscular version of Taylor; then he meets the real Taylor, and is strangled by him.

Instead, disappointingly, they both survive, and go to mass at St. Patrick's.

The mass itself is interesting to me as a Catholic. This was the era in which the liturgy, which had remained unchanged for centuries, was modified and translated into the vernacular. The mutants' worship service reminds me very much of going to church as a young kid, when such usages were still a novelty, and felt banners abounded. It's interesting how, of all things, science fiction is sometimes the most effective time capsule.

Beneath explores various forms of fanaticism and religious extremism, mostly in unimaginative ways, though I do like the idea of mutants worshiping The Bomb as the alpha and omega, the beginning and the end. It ends with Taylor detonating the bomb, destroying all life on earth. The final exchange between Taylor and Dr. Zaius is coldly cynical, and the ending is unrelentingly fitting. But, disappointingly, the screen fades to white instead of showing a special-effects nuclear blast. Even Dr. Strangelove has some mushroom clouds. Couldn't they at least have found some stock footage?

Interesting trivia: the actress who plays the telepathic mutant Albina (Natalie Trundy, the wife of producer Arthur P. Jacobs) went on to play Dr. Stephanie Branton in Escape and the chimpanzee Lisa in Conquest and Battle.

Escape from the Planet of the Apes (1971)

Given how unimpressed I was by Beneath, I'm surprised at how much I enjoyed Escape. It follows the lovable chimp couple Cornelius and Zira (and their colleague, who dies to save money on makeup) back in time to the twentieth century. They're captured and caged, then investigated, then celebrated, then persecuted, and finally murdered.

I see Escape as a sometimes dark, sometimes satirical exploration of American culture at the time. The paranoia of the government and the atmosphere of fear into which Zira and Cornelius are received is well portrayed. It's impossible not to reflect on then-current events, e.g., the Kent State shootings. Dr. Otto Hasslein, the President's shadowy science advisor, deeply suspects the apes and the future they represent. He soliloquizes about whether it would be right to kill them to change future history:

How many futures are there? Which future has God, if there is a God, chosen for man's destiny? If I urge the destruction of these two apes, am I defying God's will or obeying it? Am I his enemy or his instrument?The chimps' exposure to fashion and entertainment (and "grape juice plus") provides a humorous intermezzo to these more sinister proceedings. They show themselves radically out of step with the prevailing culture, which they find bewildering, reprehensible, and crude. They are a sign of contradiction and a threat to the social order.

More than anything, I find myself delighted by the relationship between Cornelius and Zira. To me, their overacted parts are merely irritating in the first installment; here, perhaps because of their isolation, they seem the most human of the characters. Zira's testimony before a government commission is the high point of the film. She is warm-hearted, humane, strong-minded, and intelligent; her more down-to-earth counterpart Cornelius is a perfect foil.

The final act centers around the birth of their child, Milo, and their subsequent flight and murder. Religious references abound. The President and Dr. Hasslein liken themselves to Herod, and the imagery surrounding the chimp mother, father, and child evokes the Holy Family. Señor Armando (Ricardo Montalbán), the circus owner who harbors the fugitives and ultimately adopts their son, presents them with a medal of St. Francis of Assisi; St. Francis was famously a lover of animals and, it so happens, the inventor of the nativity scene. The ending is hauntingly bleak.

All in all, I think this is my favorite of the sequels to Planet. But its place in the series does raise some insoluble problems of causality: Milo leads the future rise of the apes, and Zira and Cornelius owe their existence to said rise, and Milo is their child. My advice: don't think too hard about it.

Final question: Why does Escape from the Planet of the Apes remind me so much of Escape to Witch Mountain and Return from Witch Mountain?

Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972)

Conquest follows the fortunes of Milo, now named Caesar for some reason, as he is separated from Señor Armando, forced into slavery, and driven to lead a revolution.

The year is 1991. All dogs and cats have died. Apes now supply companionship and labor. For some reason that is never explained, apes from the wild are, with a little training, suited to becoming intelligent servitors in human households, and look more or less like humans in ape suits. It's like we're already in a parallel universe here.

Impacted by the pointless death of the kindly Armando and the mistreatment of his fellow apes, Caesar goes from wide-eyed amazement at the wonders of the city to disillusionment and finally rage. He teaches the apes to organize and fight, and leads a fiery revolution to overthrow the social order. The saga comes full circle as apes gain the ascendancy and humans begin their slow decline.

Where there is fire, there is smoke. And in that smoke, from this day forward, my people will crouch, and conspire, and plot, and plan for the inevitable day of Man's downfall. The day when he finally and self-destructively turns his weapons against his own kind. The day of the writing in the sky, when your cities lie buried under radioactive rubble! When the sea is a dead sea, and the land is a wasteland out of which I will lead my people from their captivity! And we shall build our own cities, in which there will be no place for humans except to serve our ends! And we shall found our own armies, our own religion, our own dynasty! And that day is upon you NOW!The ending was softened by studio demands but remains as bleak as any in the Apes cycle.

I enjoyed the stark, vaguely futuristic setting, with its broad, clean sidewalks and blocky buildings, which reminded me of a college campus and was in fact Century City, Los Angeles, with a little UC Irvine thrown in. The scope of the film is strictly local, which makes the sense of global catastrophe at the end a little hard to believe. It's too bad they didn't have more of a budget. But they took what they had and did very well with it.

I've read that Conquest was inspired by the Watts riots that took place in L.A. in 1965 and similar evidences of civil unrest and racial discord that swept the country during the years that followed. The one human worthy of the viewer's sympathy (other than the unfortunate Armando) is MacDonald, an African American to whom Caesar appeals for understanding of the apes' plight specifically because of his race.

The use of apes as stand-ins for minorities is effective but troubling on a number of levels. Unlike species (or sexes), races are not discrete, mutually exclusive categories, but the fact that the apes seemed a fitting symbol reflects a cynical belief that they may as well be. Tension mounts throughout the movie, and in the end no real reconciliation seems possible: once man no longer dominates ape, ape must dominate man.

At any rate, Conquest is a movie that isn't afraid to tackle current events and controversy. Nowadays when a movie explores an old issue with a level of caution that filmmakers forty or fifty years ago might have thought timid, people treat it a some kind of triumph of courage. It's something I've been appreciating about science fiction movies from this era: where filmmakers in the eighties were content to retreat into safe actioners, those in the seventies were all about pushing the envelope.

Now, here the Apes cycle should have come to its bitter end, but instead the world received

Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973)

about which, the less said, the better. I might have enjoyed this movie if it had made an iota of sense, hadn't been riddled with errors and inconsistencies, and hadn't culminated in an epic battle between a handful of humans driving extremely slow-moving yellow school bus and a smallish mob of poorly armed apes living in tree houses in what looks like some California state park.

I will say this for it: the background paintings for the ruined city are pretty good looking. But, overall, it's a terrible, terrible movie. Bizarrely, its framing device features the legendary John Huston dressed as an orangutan and speaking to a group of children. He would star in Chinatown only a year later. Maybe he just wanted to wear the makeup? Who knows.

Aftermath

For the most part, I enjoyed the Apes movies. They're a snapshot of America at a certain point in time, and don't shy from dealing with delicate issues like religion, nuclear proliferation, race relations, governmental intrusion, antiestablishment movements, women's rights, and the treatment of animals. Causally speaking they're a bit like that Escher staircase that goes up and up and leads back to where it started, but in a way that only adds to their mythic dimension.

So here's how I rank them:

- Planet of the Apes

- Escape from the Planet of the Apes

- Conquest of the Planet of the Apes

- Beneath the Planet of the Apes

- Battle for the Planet of the Apes

Tuesday, September 22, 2015

The Best of BCS, Year Six

The Best of Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Year Six e-book anthology is now out! It has twenty-two stories from the sixth year of BCS, including my story "At the Edge of the Sea."

BCS is also running a sale on the anthology at Weightless Books. Any reader who buys Best of BCS Year Six from WeightlessBooks.com will get a coupon for 30% all other BCS titles at Weightless, including other anthologies, back issues, and BCS subscriptions.

My story "At the Edge of the Sea" was inspired by Rachel Carson's books about marine life (e.g., At the Edge of the Sea), Adolf Portmann's Animal Forms and Patterns, Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, and childhood collecting expeditions on the Gulf coast with my biology-teacher father. The backstory owes a bit to the banishments that took place during the reign of Augustus.

But more than anything, in my opinion, here's just not enough fiction about horseshoe crab sex out there; I'm doing my part to fill in that gap.

The Best of BCS, Year Six features such authors as Yoon Ha Lee, Helen Marshall, Richard Parks, Gemma Files, Seth Dickinson, Benjanun Sriduangkaew, and Cat Rambo.

It includes "No Sweeter Art" by Tony Pi, a finalist for the 2015 Aurora Awards and 2015 Parsec Awards, and "The Breath of War" by Aliette de Bodard, a finalist for the 2014 Nebula Awards.

The Best of Beneath Ceaseless Skies Online Magazine, Year Six will be available in September for only $3.99 from major ebook retailers including Kindle, Barnes & Noble, iTunes/iBooks, Kobo, WeightlessBooks.com, and more.All proceeds from the anthology go toward supporting such humble wordsmiths as yours truly. Click here for more purchase information.

BCS is also running a sale on the anthology at Weightless Books. Any reader who buys Best of BCS Year Six from WeightlessBooks.com will get a coupon for 30% all other BCS titles at Weightless, including other anthologies, back issues, and BCS subscriptions.

My story "At the Edge of the Sea" was inspired by Rachel Carson's books about marine life (e.g., At the Edge of the Sea), Adolf Portmann's Animal Forms and Patterns, Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, and childhood collecting expeditions on the Gulf coast with my biology-teacher father. The backstory owes a bit to the banishments that took place during the reign of Augustus.

But more than anything, in my opinion, here's just not enough fiction about horseshoe crab sex out there; I'm doing my part to fill in that gap.

Saturday, September 5, 2015

Red Harvest and Dark Knight

I recently re-read Dashiell Hammett's Red Harvest for the nth time. It's one of my favorite books. For a great many years I've been a fan of such movies as Yojimbo and A Fistful of Dollars, whose plots feature a nameless protagonist of dubious uprightness who strolls/rides into a town rotten with corruption, plays the ringleaders against one another, using them to conduct a fiery, bloody purgation, and leaving the clean but significantly depopulated community to the survivors. Red Harvest is, as far as I can tell, the basic template for such films.

The nameless Continental Op comes into the dreary, corrupt "Poisonville" on a routine job, but when things go awry and an attempt is made on his life, he vows to open it up "from Adam's apple to ankles." And he does, pitting gangster against gangster in a war that escalates from shots in the dark to pipe bombs and machine guns, until the last pair shoot each other's guts out and the national guard is being called in to restore order. It's all so beautiful it brings tears to my eyes.

The Op describes his mode of operation to Dinah Brand, the goddess-muse-fury of Poisonville:

On the other hand, I'm an admirer of Christopher Nolan's Batman films. I'm not big on superhero films, but I like DC Comics, and Batman in particular. Always have. It's the fashion nowadays to speak rather dismissively of the Nolan films and of dark, gritty superhero films in general, and I get that – the style is hard to do right, and very bad when done wrong. But I tell you what, we'll be talking about the Dark Knight Trilogy long after all the others being made right now are forgotten. Christopher Nolan, Emma Thomas, etc., did something no one else has succeeded in doing: they made a single-focus superhero film series with a clear beginning, middle, and end – a complete plot arc – with no loose ends and no chance of continuation. And, what's more, they did something beautiful with it.

Really, the DKT is not best understood as a set of superhero films. They stand more in the realm of fantasy. I think of them as film noir meets mythology. I've commented before on the Man With No Name and the ways in which Batman fits that role. (Cf. The Man With No Name; The Dark Knight; The Harrowing of Gotham.)

Recently, though, just after having finished Red Harvest, I was watching The Dark Knight (which I do with embarrassing frequency), and I noticed something that I'd never seen before: its narrative structure is not unlike Red Harvest and its cinematic descendants, but Batman doesn't play the Op's role. The Joker does. Batman is one of the powers pitted against the others! Did I just blow your mind?

But look at it. The Joker has no name and no history. This is emphasized by Jim Gordon while he's in the holding cell at MCU. (In the comic books he had various backstories, which arguably is the same thing.) In his dialogue with Harvey Dent – one of the great scenes of film – he says:

Of course that's not all there is to the movie. For one thing, the Joker clearly did not set out with that in mind. He seems to want to establish a new order, the order, not of organized crime and police corruption, but of insane supervillainy. That he fails is Batman's victory; but that Batman and Commissioner Gordon have to base the new peace on a lie is the Joker's even greater victory.

The Dark Knight films are truly noir. They are consistently ambivalent about the role of Bruce Wayne / Batman. Consider, for instance, that in each of the first and third films, it's a Wayne Enterprises invention that threatens the city. And Batman himself is arguably to blame for the escalation in urban violence and the rise of the Joker.

At any rate, it's interesting to see the plot structure of Red Harvest appear as a subordinate component of a recent film.

|

| "Baxter's over there, Rojo's there, me right smack in the middle." |

The Op describes his mode of operation to Dinah Brand, the goddess-muse-fury of Poisonville:

"Plans are all right sometimes," I said. "And sometimes just stirring things up is all right if you're tough enough to survive, and keep your eyes open so you see what you want when it comes to the top."In other words, he's an agent of chaos.

On the other hand, I'm an admirer of Christopher Nolan's Batman films. I'm not big on superhero films, but I like DC Comics, and Batman in particular. Always have. It's the fashion nowadays to speak rather dismissively of the Nolan films and of dark, gritty superhero films in general, and I get that – the style is hard to do right, and very bad when done wrong. But I tell you what, we'll be talking about the Dark Knight Trilogy long after all the others being made right now are forgotten. Christopher Nolan, Emma Thomas, etc., did something no one else has succeeded in doing: they made a single-focus superhero film series with a clear beginning, middle, and end – a complete plot arc – with no loose ends and no chance of continuation. And, what's more, they did something beautiful with it.

Really, the DKT is not best understood as a set of superhero films. They stand more in the realm of fantasy. I think of them as film noir meets mythology. I've commented before on the Man With No Name and the ways in which Batman fits that role. (Cf. The Man With No Name; The Dark Knight; The Harrowing of Gotham.)

Recently, though, just after having finished Red Harvest, I was watching The Dark Knight (which I do with embarrassing frequency), and I noticed something that I'd never seen before: its narrative structure is not unlike Red Harvest and its cinematic descendants, but Batman doesn't play the Op's role. The Joker does. Batman is one of the powers pitted against the others! Did I just blow your mind?

But look at it. The Joker has no name and no history. This is emphasized by Jim Gordon while he's in the holding cell at MCU. (In the comic books he had various backstories, which arguably is the same thing.) In his dialogue with Harvey Dent – one of the great scenes of film – he says:

Do I really look like a guy with a plan? You know what I am? I'm a dog chasing cars. I wouldn't know what to do with one if I caught it! You know, I just... do things. [...]

I just did what I do best. I took your little plan and I turned it on itself. Look what I did to this city with a few drums of gas and a couple of bullets. Hmmm? You know... You know what I've noticed? Nobody panics when things go "according to plan." [Finger quotes!] Even if the plan is horrifying! If, tomorrow, I tell the press that, like, a gang banger will get shot, or a truckload of soldiers will be blown up, nobody panics, because it's all "part of the plan." But when I say that one little old mayor will die, well then everyone loses their minds! [Hands Dent a gun and points it at himself.] Introduce a little anarchy. Upset the established order, and everything becomes chaos. I'm an agent of chaos. Oh, and you know the thing about chaos? It's fair!By the end of the movie, the three big gangsters are all dead, their money is torched with their launderer, the corruption on the police force is exposed, the national guard is called in to restore order, and Batman is driven out as a pariah. If the Joker had set out specifically to clean up Gotham, he couldn't have been more efficient.

Of course that's not all there is to the movie. For one thing, the Joker clearly did not set out with that in mind. He seems to want to establish a new order, the order, not of organized crime and police corruption, but of insane supervillainy. That he fails is Batman's victory; but that Batman and Commissioner Gordon have to base the new peace on a lie is the Joker's even greater victory.

The Dark Knight films are truly noir. They are consistently ambivalent about the role of Bruce Wayne / Batman. Consider, for instance, that in each of the first and third films, it's a Wayne Enterprises invention that threatens the city. And Batman himself is arguably to blame for the escalation in urban violence and the rise of the Joker.

At any rate, it's interesting to see the plot structure of Red Harvest appear as a subordinate component of a recent film.

Thursday, September 3, 2015

Donald Trump and Me

All my life I've been telling myself that one day – one day – I would share the front-page news with Donald Trump. Well, my friends, that day has arrived.

Yes, that's the nice thing about living in an out-of-the-way place. There's a pretty low bar for making the news. As you can see, I even made it above the fold. (Well, partially.) Which underscores something that seems rather quaint by today's standards: where I live, if you want to know what's going on, you have to get a print newspaper subscription. Crazy!

The article is in Q&A format. Even if you read this blog only on rare occasions, most of it will be no news to you. It gets my workplace wrong (I work at a university, not a junior college), but that only serves to keep my real-life persona shrouded in shadows of disinformation, much like Batman.

I offer the article mainly as a curiosity, because I feel fairly certain that this is the first time a magazine like Beneath Ceaseless Skies and (possibly) the Hugo award have made the news in my region.