Because this is my blog, where no one can stop me from doing whatever I like, I've posted a bunch of pictures taken with my digital microscope. Here are some of the highlights:

See the rest on the microscopy page.

Monday, November 30, 2015

Thursday, November 19, 2015

Rites of Spring

I should have been a pair of ragged claws

Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.

Life on earth is divided into three main phases: the Paleozoic Era, the Mesozoic Era, and the Cenozoic Era. The Cenozoic is the most recent, and saw the dominance of mammals and the evolution of man. The Mesozoic is most famous for the dinosaurs.— "Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock"

|

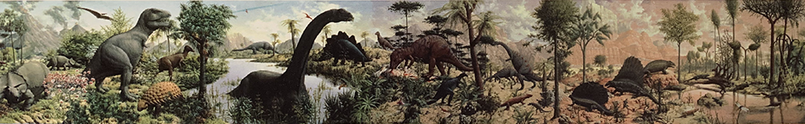

| Rudolph Zallinger's 1947 Age of Reptiles mural at Yale University. I had a copy of this on my bedroom wall when I was a kid. The right-hand part inspires my writing. |

I've also always been drawn to lower life-forms, like mosses and marine invertebrates, which dominated in the Paleozoic.

|

| From Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur. |

|

| An artist's 1906 rendering of a coal swamp with tree ferns, scale trees, and giant scouring rushes. |

|

| Image from Disney's Fantasia (1940). |

|

| Tiffany stained glass window (c. 1890). |

Through the desolate summits swept ranging, intermittent gusts of the terrible antarctic wind; whose cadences sometimes held vague suggestions of a wild and half-sentient musical piping, with notes extending over a wide range, and which for some subconscious mnemonic reason seemed to me disquieting and even dimly terrible. Something about the scene reminded me of the strange and disturbing Asian paintings of Nicholas Roerich, and of the still stranger and more disturbing descriptions of the evilly fabled plateau of Leng which occur in the dreaded Necronomicon of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred.Do you see what we've done? We've made a complete circle: Paleozoic → Chthulu mythos → Nicholas Roerich → The Rite of Spring → Fantasia → Paleozoic.

|

| A member of the Great Race of Yith [source] featured in "The Shadow out of Time." |

|

| One of Roerich's backdrop designs for The Rite of Spring. |

This makes metaphors rather difficult. Can one say that the wall of an ancient crypt is "honeycombed" with tombs, or that an old man is "waspish"? Are airships flown by "aviators"? Are the embarrassed allowed to be "sheepish"? Can the recalcitrant be "cowed" into submission? Is there a "bloom" on a young girl's cheek? Can an oaf make "asinine" comments? Can dawn-tinted clouds wear a "rosy" hue? Do cozening enchanters speak "mellifluously"? Do mighty warriors flex their "muscles"?

Indeed, how far does one go in "winnowing" out words with connotations that violate the rules of the world? As a person who consults an etymological dictionary on a regular basis, I could go crazy fretting about things like this. In the end, I suppose it's all a matter of ear. Whatever you do, the important thing is to not call attention to it. Still, it's worth noting that the great fantasists generally are very careful about word choice.

J. G. Ballard's strange and lovely Drowned World, which I just finished reading, is another literary work featuring the Paleozoic. Though framed as a post-apocalyptic tale, it centers around man's evolutionary regress to a still-present genetic past.

In The Sea Around Us, marine biologist Rachel Carson claims (with what truth I know not) that the chemical composition of human blood represents the salinity of the primordial seas from which our amphibious forebears arose. And zoologist Adolf Portmann discusses in Animal Forms and Patterns how widely differing species share similar embryos, so that the first stages in the development of a man are almost indistinguishable from lower vertebrates and even arthropods. We are still as segmented as millipedes in our backbones.

|

| Trilobites, eurypterids, and horseshoe crabs, from Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur. |

for

yourself, sir, should be old as I am, if like a crab

you could go backward.

— Hamlet

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)