This is a continuation of my Arts of the Beautiful post. Here is

Part I, and here is

Part II. We formerly noted four marks required by our interlocutor in a work of art:

- The work must require skill.

- The work must represent an object from nature.

- The work must evoke an emotion.

- The work must refer to something.

Thus far we have considered the first three. To the first we replied that skill is an accidental though humanly necessary quality, but that the skill of the artist is not precisely the same as the skill of the draftsman; also, apparent ease of execution my be the fruit of years of discipline. To the second we replied that the requirement to closely imitate physical objects in pigment confuses the categories of Art and Nature, identifying the beauty of the subject with the beauty of the painting; but we also suggested that no painting worthy of the name can be truly independent of nature, however high the degree of abstraction. To the third we replied that mood and emotion are inherently subjective, and that the only relevant emotion is the pleasure that comes from seeing a beautiful object made by hand.

So, on to the fourth mark.

Art and Word

The objection to a piece of art on the grounds that it does not refer to something is the objection of the

writer. Critics and art historians are, occasionally, philistines, unable to appreciate a painting for its purely visual qualities, but their breadth of knowledge, urbanity, and circumspection make them much more difficult to detect than their less-refined country cousins.

The reason art-writers are sometimes philistines is quite simple: their trade consists of blather, and if a painting doesn't

say something or

express something then there's not much blather to be gotten out of it. A mute does not need an interpreter. So paintings are made to say things.* Which, by the way, they often do; only, their beauty does not flow from the artist's ideas or feelings.

Though art-writers often speak authoritatively, they rarely say anything about craftsmanship or visual appearance, which is, I think, very telling. But what indeed could really be said without sounding pedestrian? And when they do comment on visual impressions, their opinions generally boil down to, "I like this, and you should, too," or, "I don't like this, and neither should you." As such they serve a humble but important function. Find a critic whose tastes conform to your own, and you can save yourself the trouble of attending an exhibition you're not likely to enjoy. But that's the extent of their role, if what we're talking about is truly

visual art.**

As to that, I confess that I find it a little peculiar to hear the objection to non-referential art from someone who decries such insults to civilization and intelligence and the tax-paying public as

Piss Christ. Because it's this tragic confusion of art with communication that has led to the scourge of conceptual art, which is

pure communication, in reality a pretentious form of drama masquerading as art, with the artist as star or prophet.

Here is where I take a low view of modern art, which seems to me to have lost its way, with artists deliberately setting out

to make for purposes

wholly divorced from and sometimes

diametrically opposed to visual harmony.

I recently attended a gallery opening featuring the work of an MFA student. I thought the pieces (collages, mostly) visually arresting and skillfully executed. But her artist's statement explained that she seeks to combine

bad art with

good art. Surely one needn't obtain an MFA to do that! Really I suppose that her statement is a coded message, and that by bad art she really means "bad art," i.e., art perceived by the arts community (or rather, the arts-appreciating but not quite with-it public viewership) as kitsch. Because what she's clearly doing is attempting to transform this "bad art" into something worth looking at.

If I were to take her at her word, though, I'd have to conclude that she's actively striving to vitiate the end to which she aspires to attain. It's like a mountain-climber giving out that he seeks to combine good with bad mountain-climbing, deliberately blundering into blind ravines and tumbling down slopes in order to make an ironical statement about the lowbrows who just climb competently to the top. You see, once he admits that mountain-climbing is no longer his primary end, he becomes

something other than a mountain-climber. I can just imagine an artist, in dismissing some of her older work, saying, oh, that was my naïve

good phase, when I only produced

good work; I've moved past that now, into my more mature

bad phase! As I say, I

don't take this particular artist at her word, because her craftsmanship says otherwise, but there certainly have been many artists who did set out to produce either bad art or something that isn't art at all, to jab a thumb in the eye of the bourgeois, their great forerunner being "R. Mutt" and his famous

Fountain.***

Here we have the decline of civilization! Here I earn back a bit of my curmudgeon street cred. I remember seeing a piece that consisted of Pieter Brueghel's 1563

Tower of Babel printed on a curved sheet of metal with a big piece of stovepipe or dryer hose coming out. This is just as derivative and impoverished as the statues of the late Roman emperors that recycled the old bodies of gods and heroes created in times of higher cultural attainment, replacing their heads with crude new caesars' heads. But at least Constantine wasn't

pretentious about it.

To me there's nothing duller and more demoralizing than seeing a bubbling glass bowl with glowing thingees, or stacks of clay tiles on the floor, or chains of communion wafers dangling from suspended bones, or a stuffed goat with a rubber tire around it, and thinking, okay, what's this supposed to be? And then reading the placard, and saying, oh, I see. Boring and annoying.

These little artefacts are not necessarily

bad, mind you. They're just not

visual art as I use the term. They're a form of communication or drama. In fact, these items are

nothing apart from the chatter that surrounds them, and exist as a kind of

fiat currency or line of trading cards for the cultural elites, with critics serving as the guarantors of validity. I wrote about the matter at some length in my post

Arts of the Ugly, which is a kind of appendix to this series.

Abstract art, though, is not a case of the Emperor's New Clothes. It is, rather, an attempt by artists to recover the essence of painting, which consists, not in trompe-l'oeil effects and topical allusions, but in being pleasing to the eye.

The extraordinary modern adventure of abstract art precisely expresses the decision, made by certain artists, to turn out works whose beauty will obviously owe nothing to that of the subject. [Arts of the Beautiful]

Vuillard, Whistler, Matisse, Mondrian, Klee, O'Keefe and the rest did not set out to create objects that offend the eye and accustom man to ugliness. Quite the contrary. They stand on the side of beauty. Marcel Duchamp's urinal militates against their project just as surely as it does against the Pre-Raphaelites'.

Beauty and Truth

Those who insist that paintings must

look like something or

say something true, or else face the charge of irrationality, are making a mistake in conflating the transcendentals of Beauty and Truth, which are not reducible to one another. Beauty is truth, truth beauty, but the truth of beauty is not the beauty of truth.

There is a tendency, among those with a philosophical or logical bent, to try to annex every branch of human activity into some form of inquiry, and they are particularly discomfited to find judgments of beauty beyond the reach of their syllogisms. But the true philosopher recognizes the limits of his methods. We may philosophize

about art, as about anything, and debate its nature, as we've done here, but as to giving a formal logical

proof of why one painting is better than another? No.

How indeed would such a proof go? "Well, this painting is bad because it violates such-and-such law." What law? Who says it's a law? Why should I regard it as universal? One can certainly

argue that a given painting is no good, and list the reasons, and perhaps persuade the undecided. But no formal deductive proof is possible without axioms, and the "science" of the beautiful is simply not an axiomatic science. Any "laws" we erect are necessarily

ad hoc, and liable to be violated by a master of his craft.

There's an element of the subjective in the perception of beauty. This seems obvious, but apparently it needs to be said. Beauty is, in a manner of speaking, in the eye of the beholder. This wouldn't be a cliché if there weren't some truth to it. Perceptions vary from person to person. If someone thinks a picture beautiful then you can abuse their judgment but you can't really argue with them. This is not to say that beauty is

purely subjective, as some might claim. When deconstructionists assert that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder," they really mean that there

is no beauty except what people choose to call beauty. I'm not saying that at all. No, the beauty is in the

object, and if one man perceives it then we can expect others of similar tastes to perceive it as well. But just because one does

not perceive it does not mean that it is not there.

Of course, someone may be mistaken about the ends of art, and frame their judgments accordingly, and then we may argue against their position. If they say that a painting is bad because it doesn't imitate nature, evokes no emotion, and communicates no idea, then we may reply that they aren't really talking about the beauty of art at all, and may in fact be insensible to such beauty, as the tone-deaf are insensible to music. If they say that a painting is bad because it's butt-ugly in a purely visual sense, then we may privately opine that they have a poor or unformed taste in such matters, but little remains to be said.

A Defense of Paul Klee

And now, despite everything I've just said, I'm going to attempt the thankless task of defending the work of my favorite modern artist, Paul Klee. When I say "defend," I hope by now that it's clear I don't intend to

prove his work to be good. Indeed, I hold such an endeavor to be ridiculous.

Our interlocutor has said that, while tastes differ as to the beauty of women, when he meets someone whose tastes do not coincide with his own, he can at least concede that they are both talking about women, and that there is probably something to be said for the other's preferences. The same, he says, applies to representational art.**** But when it comes to abstract painting, the differences are of kind, not of degree, and the very notion of comparing the two is so offensive to reason and common sense and human decency that it makes him physically ill with disgust. As I have argued, I think him mistaken about the nature and ends of art. However, I also think the differences

are of degree, not of kind, and this shall be made clear in what I have to say concerning Klee's art.

|

| Klee, Siblings |

Anyway, I'm at a loss to explain whence our interlocutor's disgust proceeds. I suppose that if a person has been trained that a painting should be a naturalistic picture of something they recognize, and is instead presented with some more abstract arrangement of color and form, they may receive a mild shock. But physical illness? I confess that the drawings of the mentally ill sometimes make me uneasy. But the drawings of children do not. Those of non-Western or pre-modern cultures do not. I am not offended by the cave paintings of Lascaux or the stylized depictions in Egyptian tombs. Why should I be disgusted by a Klee or a Picasso?

"Well," you might say, "it's all very well for a child or a savage to draw a naïve picture, but for an adult in full possession of his powers to do so designedly is worthy of nothing but contempt." But this tacitly assumes that our "primitive" painter was trying and failing to achieve the trompe-l'oeil effects so highly valued by our scientific civilization, and that his output, while good for its time, is but a crude approximation to our sophisticated techniques. This is, to say the least, a shallow view of art, culture, human perception, history, and pretty much everything. Some cultures may be more "mature" than others according to various metrics, but when it comes to perception of beauty

we are all children, or should be.

|

| Klee, Uncomposed Objects in Space |

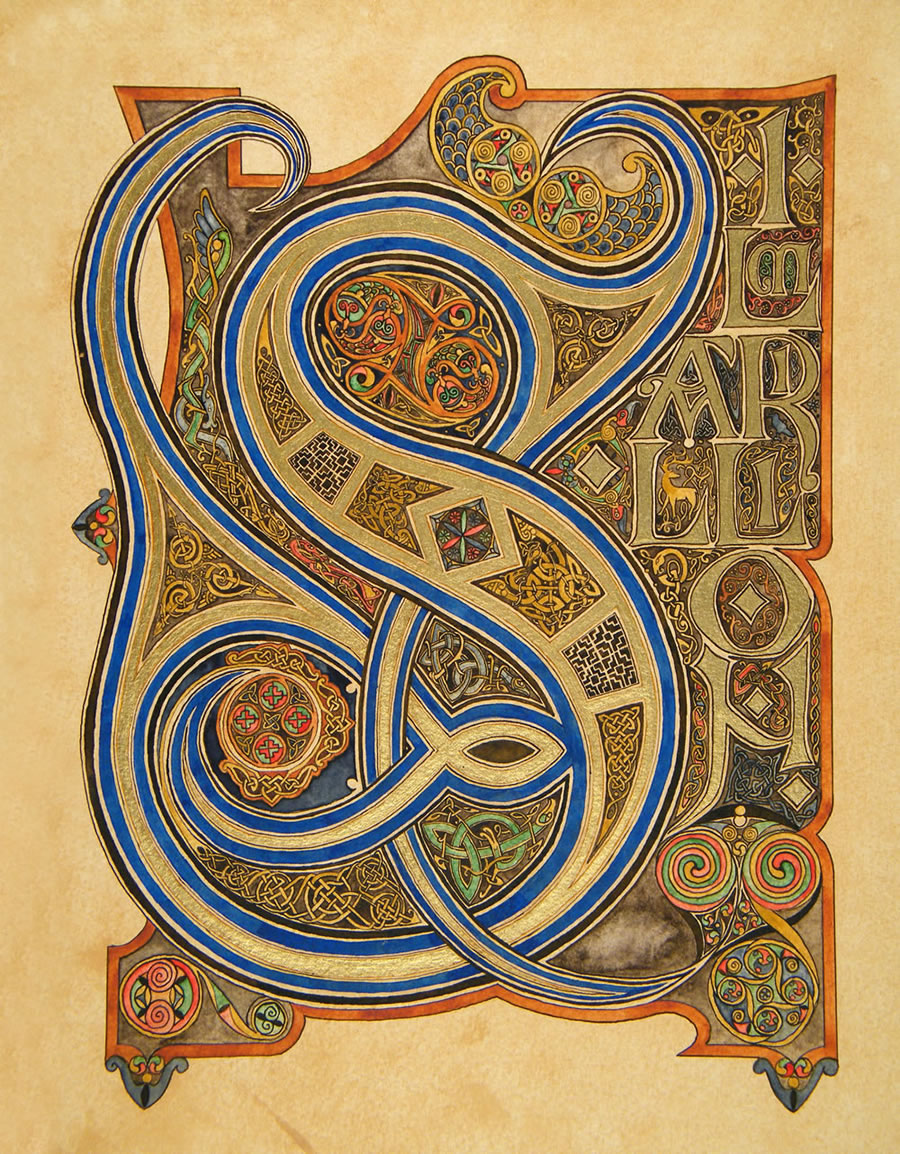

It's not uncommon for art history books to begin at the Renaissance, pretending that International Gothic doesn't even exist, or to patronize the Medievals for their flattened perspective and decorative use of color and pattern.

Let them look at Gothic Figures & Gothic Buildings, & not talk of Dark Ages or of Any Age! Ages are All Equal. But Genius is Always Above The Age. [Blake's marginalia to the works of Sir Joshua Reynolds]

Is the use of linear perspective truly more advanced? It may be more

mathematical, but from a certain point of view it

less advanced, dwelling as it does on

chance appearances to the exclusion of

what things actually are. I once saw an old photographic portrait of an Indian dignitary which had been "corrected" so as to have the richly patterned carpet parallel to the picture plane, because that's what looked more natural to the viewers for which it was intended, used as they were to

Mughal miniatures and the like. Perhaps they had a point.

So I find no reason to be disgusted by a Klee painting for being childlike, flattened, distorted, or stylized. To declare oneself unable to distinguish between a child's drawing and a madman's demented scrawl is to take a low view of children indeed. And Klee's paintings are the work of no madman, either in truth or by affectation.

|

| Klee, Mask of Fear |

Perhaps a short biography is in order. Klee married in his late twenties after a somewhat loose youth, and was for a number of years a stay-at-home husband, raising his young son Felix and keeping house while his wife worked as a piano instructor. He kept a diary (the "Felix calendar") about his son's progress, and later created a puppet theater with an array of puppets to amuse him. He made no hard divisions between the art of his own childhood and his work as a professional artist, and it was during his "happy househusband" years that he developed his approach to art. He and his wife were both talented musicians with strongly conventional inclinations.

Klee was for a time an instructor at the Bauhaus, an arts academy and community that attempted to infuse a Medieval work-ethic into modern art. As his work became better known he fell under the notice of the Nazis. He began receiving subtle threats in print that expressed disgust with his work, made sneering references to his supposed Jewish heritage, and opined that his paintings were foisted upon the public by Jewish dealers intent on financial gain. At last he was forced to emigrate to Switzerland, and there died at the age of sixty before receiving citizenship, which, despite his having been born in that country, had been delayed because of his radical, "degenerate" art.

Is this the portrait of a deranged madman, a pervert, or a conspirator against all that is good and holy? None of this says that Klee's work was any good, of course, but I think it does at least suggest that a quick dismissal on culture-war grounds is unwarranted.

Our interlocutor describes Klee's work as "random," an opinion I find strangely contrary to my own visual impressions. The artist's own elliptical attempts to articulate his theory of creation indicate an intense mental concentration, as evidenced by his short but dense

Pedagogical Sketchbook, which is, for me, a constant source of inspiration. It's well worth perusing for someone trying to form an understanding of Klee's method of creation.

|

| Klee, Signs in Yellow |

The book is divided into four parts. The first deals with the transformation of the travelling dot into the line, and of the line into the planar region. It identifies the open curve with the

active, and the planar region with the

passive, while the closed curve is referred to as

medial, standing between the two. Active: I fell (a tree with an ax). Medial: I fall (under the strokes of the ax). Passive: I am being felled (with an ax). It considers the growth of structure ("purely repetitive and therefore structural") as

frieze ornament and

lattice ornament (my terms); these can be classified mathematically, and there are exactly seven types of the first and seventeen of the second, though Klee considers only the simplest. He also ponders the golden ratio. But throughout the motif is the "trichotomy" of active, medial, passive. Active: brain; medial: muscle; passive: bone. Or: Active: anthers; medial: bee; passive: fruit.

Already at the very beginning of the productive act, shortly after the initial motion to create, occurs the first counter motion, the initial movement of receptivity. This means: the creator controls whether what he has produced so far is good. The work of human action (genesis) is productive as well as receptive. It is continuity. (Productivity is limited by the manual limitation of the creator (who has only two hands). / Receptivity is limited by the limitations of the perceiving eye. The limitation of the eye is its inability to see even a small surface equally sharp at all points. The eye must "graze" over the surface, grasping sharply portion after portion, to convey them to the brain which collects and stores the impressions.) The eye travels along the paths cut out for it in the work.

This last is significant to me. I have sometimes

wondered if my love of Klee's work is connected to my cognitive disorder, which has the effect of

hyperfocusing my attention. This inability to integrate particulars into a coherent whole is a matter of degree, however, and is part of the human condition, so I'm not suggesting that an appreciation of Klee is necessarily limited to those with this disability. But perhaps his deep understanding of perception renders his work more accessible to me than that of some other artists. Perhaps.

|

| Klee, Polyphony |

Perusing the rest of the

Sketchbook more cursorily, we have Part II [dimensionality: perspective and balance], Part III [the elements: earth/water/air and continuity, which may be rigid, rhythmic, or loose], and Part IV [symbol: the plumb-radius and logarithmic spiral; the arrow ("The father of the arrow is the thought: how do I expand my reach?"), vector addition, and gravity; color and the color wheel]. That Klee was such a sensitive colorist makes this last section especially worthy of study. It describes the role of color-flow in movement, and in particular its description of incandescence (blue to orange) and cooling (orange to blue) calls to mind

Separation in the Evening, cited in

Part II of this post. The section concludes with:

We have arrived at the spectral color circle where all the arrows are superfluous. Because the question is no longer: "to move there" but to be "everywhere" and consequently also "There!"

|

| Klee, The Goldfish |

So let's look at a couple of my favorite pictures. Here we have

The Goldfish (1925), painted in oil and watercolor on paper on cardboard. Its glowing colors achieve a profound visual effect, indicating skill in the use of mixed media. It imitates nature: its subject is clearly a fish. In me it evokes various emotions, an admixture of the dread and glory of nature, particularly of the primal oceanic black night. Admittedly it refers to nothing that I know of, save the godlike golden Fish from which all others flee in terror. But as we have said, these are all material.

What I like about it, visually speaking, is the intense electric (yet patterned)

warmth of the Fish itself, surrounded by a pool of inky black, with deep-sea-blue water plants and purple fishes around the periphery. The contrast presented by the near-complements is pleasing to the eye. The purples and blues of the border are nicely balanced (with warmer purples and reds at the corners), and the Fish, weighted toward the front, is well placed in the rectangular format. Change one of these things and the picture suffers severely. Even the shapes of the peripheral fish are well chosen. The eye begins at the Fish, circumambulates through the murky blues and reds and blacks, and finally returns to the Fish again, focusing, perhaps, on its staring pink eye.

|

| Klee, Ad Parnassum |

Another personal favorite,

Ad Parnassum (1932), is regarded by many as Klee's masterpiece. It is painted in oil, with imprinted lines and points, the points overpainted, on casein color on canvas. Once again, it exhibits great skill in the use of materials in achieving its effects. It is plainly a picture of a mountain, with the sun and the sky and something like a ruined archway in the foreground (or maybe it's meant to be a positive shape against a sea of orange light); its title, though, announces it to have a musical theme. Parnassus was, of course, the home of Apollo and the muses, and I've read that Ad Parnassum was the title of a common musical scale or exercise. It evokes in me an emotion of serenity tinged with the melancholy of twilight.

Ad Parnassum was, incidentally, my introduction to Klee's work; I first saw it in a book called

100 Famous Paintings purchased by my mother at a Target when I was a teenager. It was the only book on art history that we owned. At the time I thought the painting one of the most beautiful things I'd ever seen. I mention this because culture warriors sometimes like to ascribe a taste for such things to the influences of a warped education, whereas my own reaction was spontaneous and untutored; my study of art history in school, such as it was, had been limited to ancient art, International Gothic, and the Renaissance.

I will note here, before proceeding to the painting's visual qualities, that its musical theme is shared by a number of Klee's pictures, e.g.,

Polyphony, shown above, which is similar in execution to

Ad Parnassum but has a subtler unifying principle. Klee was, as I've mentioned, conventional in his musical tastes, but music seems to have run ahead of painting in its pursuit of abstraction, with compositions appreciable for their purely audible qualities appearing well before similar developments in the visual arts. To me it seems about as reasonable to reject a painting for being abstract as to reject something like Beethoven's Fifth. At any rate, I would argue that Klee's radical, "degenerate" art went hand-in-hand with his "conventional" tastes in music.

The painting appears constructed from roughly rectangular regions of flat color, but these regions are overpainted with dot-grids, and some of these dots colored so as to either blend in or complement their background, creating an almost miraculous shimmering effect. At the same time, the boldly imprinted lines create a strongly architectural quality. The warm foreground "ruins" lead the eye upward and to the right, to the middle of the right-hand side; then the majestic "mountain" ascending from the velvet gloaming leads the eye skyward into sunlit heights, until we come to rest at the general focal area: peak, sun, and cloud. The sun itself, a flat, dull orange, sets the rest of the colors on fire.

|

| Church, The Parthenon |

The painting's overall effect, from visual structure and color scheme to mood and theme, is, to me, comparable to Frederick Edwin Church's 1871 painting of the Parthenon. The color here is not as saturated as in a book I own, so the effect of the colors isn't quite the same as what I'm referring to, though of course you can't ever really trust reproductions.

Well, perhaps this is as good a place as any to stop. Klee's output was massive, and it's not uncommon to pick up two monographs with little intersection. Some of his pictures are, in my opinion, not as successful as the ones I've presented here, but he never ceased experimenting with styles and materials.

It seems appropriate to end with his own words:

Presumptuous is the artist who does not follow his road through to the end. But chosen are those artists who penetrate to the region of that secret place where primeval power nurtures all evolution.

There, where the power-house of all time and space—call it brain or heart of creation—activates every function; who is the artist who would not dwell there?

In the womb of nature, at the source of creation, where the secret key to all lies guarded.

But not all can enter. Each should follow where the pulse of his own heart leads. [Paul Klee on Modern Art]

Or, as a final epigraph:

Art does not reproduce the visible;

rather, it makes visible.

* Rather, recent paintings are made to say things. In books of art history, old paintings are reduced to sets of allusions. If you want to get really depressed, pick up a fine art history book put out by Phaidon or some such publisher and actually read the garbage they print in the white space left over by the pictures. The historical, scriptural, and mythological tidbits trotted out (cloppety-cloppety-clop) by the people they find to write these things seem to have come from hazy memories of the appendix at the back of the workbook they were given in their undergraduate art appreciation class. A book I have on Piero della Francesca, for instance, solemnly states that Christ's family "settled in Jerusalem." Another, a book on the Pre-Raphaelites, explains that Rossetti's painting of the Annunciation was controversial because it places a halo around the dove, which was an unconventional treatment for "animals" at the time. This was, it seems, the author's own construction. No evidence of controversy is given, nor any sign that the author has the least familiarity with the countless paintings of the same subject produced throughout Europe from the Middle Ages on.

** I'm speaking of art criticism here, not literary or film criticism; fiction doesn't seem to fit neatly into the category of arts of the beautiful, and the problem of identifying the causes of failure or success is a manifold one, requiring considerable powers of reason.

*** The original, I mean, not the limited-edition replicas, which are priceless art treasures to be protected at all costs from being used for their apparent purpose.

**** A comparison fraught with danger for two reasons. First, women are human persons, not objects, whereas paintings are objects. Second, an appreciation for the beauty of women involves an element of sexual desire, whereas an appreciation for the beauty of a painting as such is purely intellectual. It has been pointed out that there are no tactile, olfactory, or gustatory arts of the beautiful because these senses are too involved in the animal appetites, which run toward sex and food (as observed by Aquinas, I believe). Only visual and auditory arts are possible. The admiration of a cheesecake picture or an actual physical body involves, at least unconsciously, an imaginary physical encounter, and so takes place on a different plane from the disinterested pleasure evoked by a beautiful painting.